This is how FaMe-Net works

Explanation of the FaMe-Net registration, the data recorded and the concepts used in the registration.

Scroll direct to content on this page:

Or click here for more information of our organisation.

Introduction to the FaMe-Net registration

This website provides primary care morbidity data from Family Medicine Network (FaMe-Net), a practice-based research network (PBRN) located in the Netherlands. FaMe-Net is the world’s oldest and still functioning PBRN. The network is a continuation of two well-known Dutch predecessor PBRNs from which it originated after their fusion in 2013: the Continuous Morbidity Registration Nijmegen (CMR) registering epidemiology since 1967, and the ‘Transition Project’, registering since 1985.

FaMe-Net general practitioners (GPs) provide regular primary care to their listed patients. Registering for the PBRN occurs simultaneously and in the context of the Dutch healthcare system. The PBRN registration is performed for research and educational purposes.

FaMe-Net registers ‘complete’ morbidity, i.e. all morbidity that patients present to their GP. Data are collected continuously and longitudinally.

The participating GPs record morbidity (and other items) in their Electronic Health Record (EHR) named TransHIS, that was specially designed for the extensive data registration, facilitating education and research.

The data shown on this website are a selection of FaMe-Net’s most essential data. Concepts and terminology will be explained below. Data are extracted and periodically updated. The FaMe-Net registration is innovative, with ongoing evolvement, and contains more items than those shown on the website in the current version. As parallel processes, this website is continuously in development, with periodical addition of latest collected data, and with planned addition of more collected variables. We showed the innovations and the expansion of the FaMe-Net registration from 2016 onwards in a peer-reviewed publication.

Click here for more information on the organisation of FaMe-Net: its historic background, the Dutch health care system, participating practices, and scientific output.

Data from the FaMe-Net database are available since 2005. Since then, all data within FaMe-Net have been uniformly classified according to ICPC-2.

Data on the website and in the textbook chapters are presented from 2014 onwards. Since then, the network and the registering practices have remained quite stable which is important for the epidemiologic description of morbidity. The fusion in 2013 resulted in a significant expansion of the total study population. With more relatively young patients joining, the age distribution of the entire population changed, resulting in a smaller proportion of the 75+ group. Occasionally, individual registering practices may join or leave the network.

Currently, data have been updated up to and including 2021, derived from six family practices (35 GPs). In these practices, more than 41.000 patients were registered at the end of 2021.

The latest update of the website has been performed in June 2023.

FaMe-Net has shown to provide high-quality data derived from an unselected population.

FaMe-Net performs systematic quality checks of the stored data and provides registration feedback to GPs, e.g. in the registration of malignancies and deaths. Uniformity in registration of diagnoses, RFEs and interventions is achieved through continuous training and quality control programs for GPs (in training), practice assistants and practice nurses (POHs).

Since 2016, FaMe-Net has started to collect contextual and personal characteristics of all the listed adult patients in a structured way. Addition to the website of some variables collected in this way is planned.

Registered data in FaMe-Net

Below we describe the registered data in FaMe-Net and essential concepts to record them.

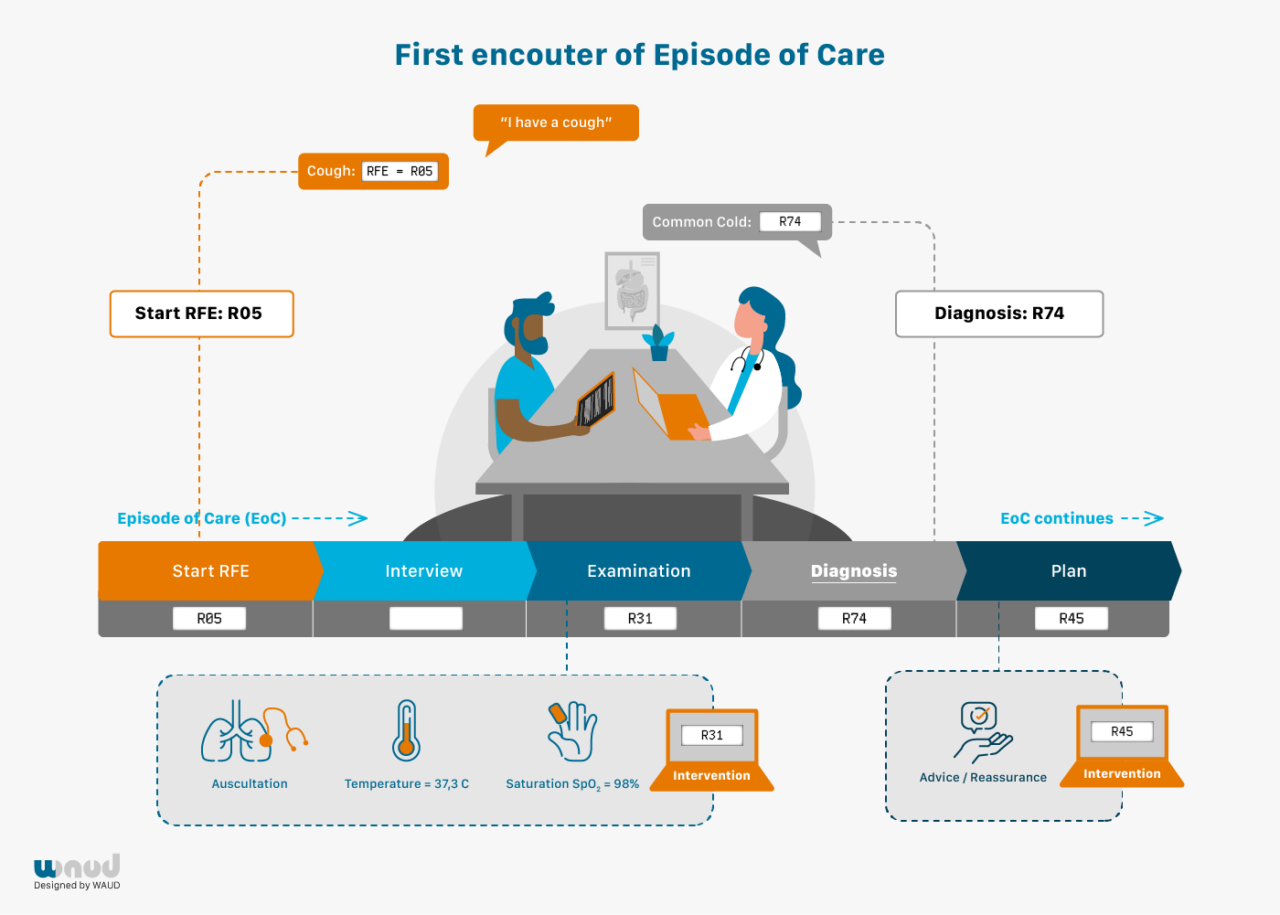

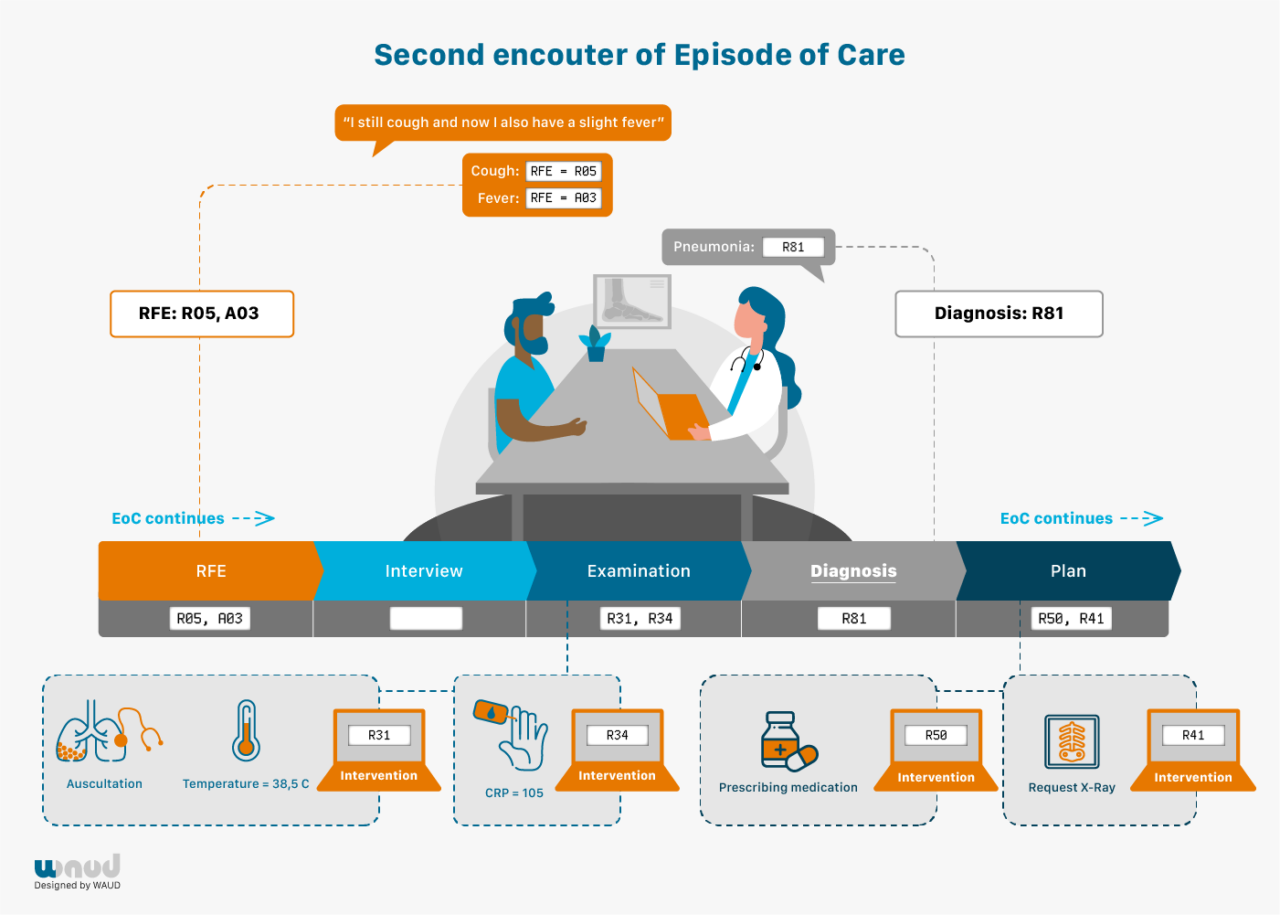

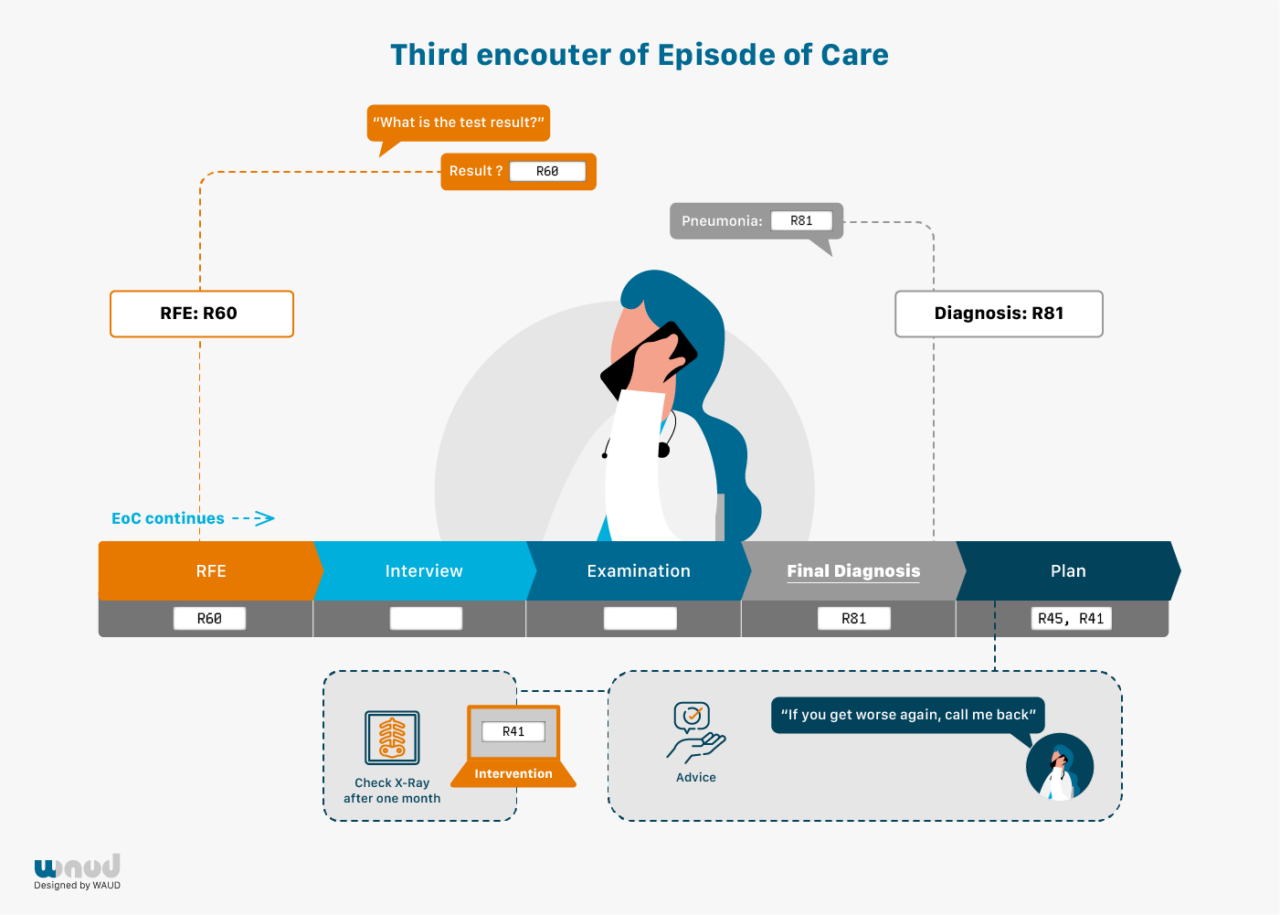

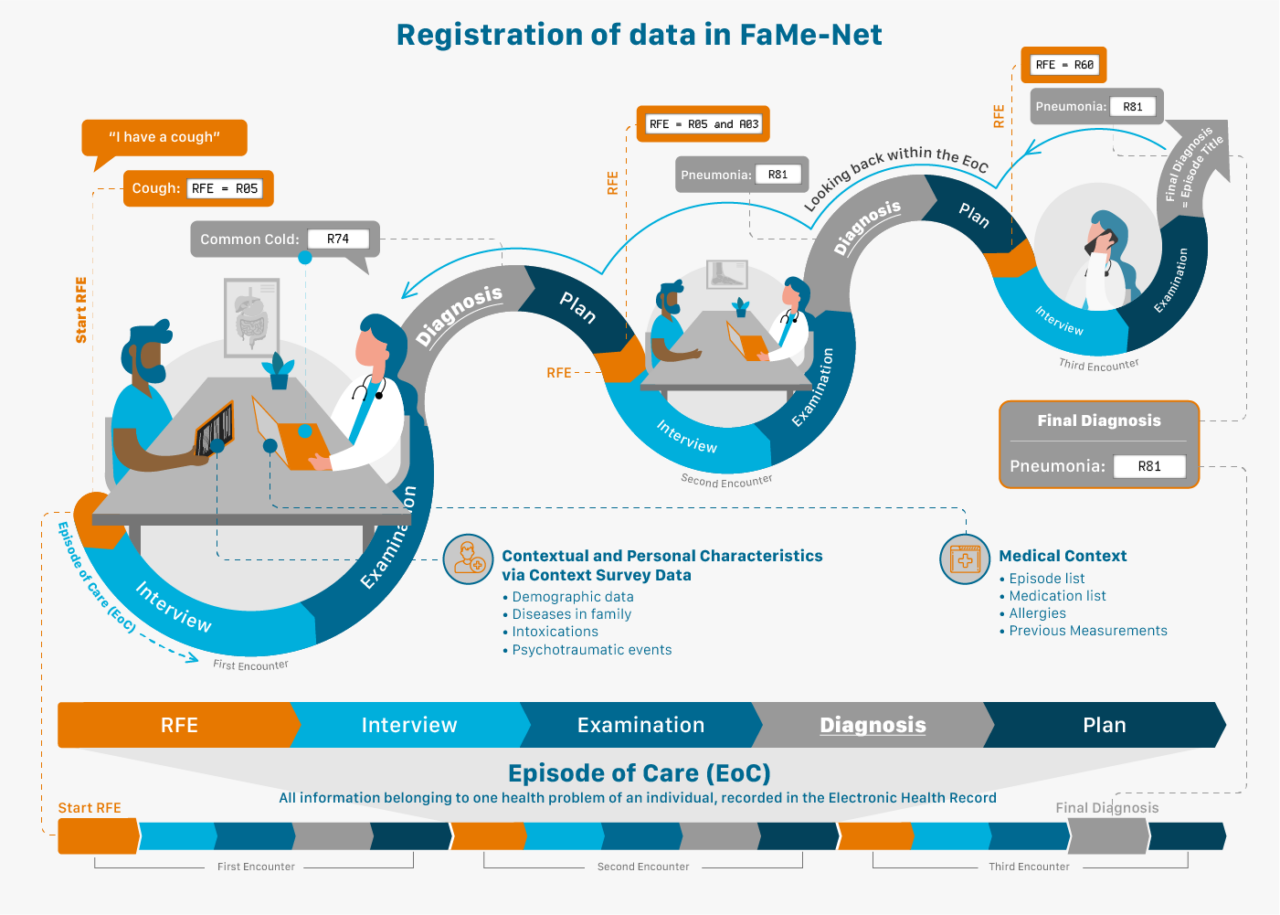

In each encounter, the reason for encounter (RFE) and the diagnosis (episode) are mandatory items to record. Interventions (e.g. diagnostic interventions, prescriptions, referrals) are recorded in any encounter in which they occur.

The core concept within FaMe-Net is the Episode of Care (EoC): all data in FaMe-Net are ordered into Episodes of Care. It can be defined as ‘a health problem presented by an individual to a healthcare provider, from the first presentation until the last encounter’. EoCs have a title, the episode diagnosis, classified with ICPC-2. The episode diagnosis can be modified during the EoC. An example: an EoC is first labelled as fatigue, but the diagnosis (episode title) is changed to iron deficiency anaemia, and it later appears to be caused by colon cancer, which will be the final diagnostic label. All contact elements related to this health problem are comprised in this EoC, including specialist reports to the GP.

Presented data from ‘Episodes of Care’ are abbreviated to ‘Episodes’ on this website.

Another essential concept used in FaMe-Net is the Reason for Encounter (RFE).

Patients normally start the consultation with a spontaneous statement on why they visit the doctor: the Reason For Encounter. This reflects the initial presentation of the illness. This statement precedes the interaction between patient and GP, and the GP’s interpretation. RFEs are recorded regardless of the final diagnosis. FaMe-Net routinely and systematically registers all RFEs in all encounters during regular consultations, taking GPs less than a minute of time.

The RFE(s) can be presented as a symptom (e.g. abdominal pain, a rash, cough), but also as a self-diagnosed disease (‘I’ve got the flu’; ‘I think I have migraine’; ‘I hope it’s not pneumonia again’) or a request for a particular intervention (‘I would like to have a blood test’). When multiple RFEs are presented, all are registered. The RFE(s) should be recognised by the patient as an acceptable description of the demand for care. RFE registration enables research studying associations between RFE and (final) diagnosis. RFEs in themselves have important prognostic value, for example in diagnosing cancer. (3, 4)

All presented symptoms, complaints, diseases, and problems in FaMe-Net are classified by the GP in accordance with the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC-2) at the highest level of accuracy and understanding. In addition to ICPC-2, diagnoses are also coded with the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10).

Transfer to ICPC version 3 is planned, now that it has been released in December 2020. This will allow for additional recording of functioning (activities and participation) and personal preferences linked to morbidity.

All interventions (processes) are also coded with ICPC-2. Diagnostic and therapeutic interventions may be distinguished. Diagnostic interventions include measurements in physical examination (e.g. blood pressure measurement). Therapeutic interventions include referrals, prescriptions, vaccination or surgical procedure.

Prescriptions are coded according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) coding system maintained by the World Health Organization.5

Prescription data provide detail and are a particularisation of the intervention type ‘medication’ (ICPC-2 code *50).

Prescription data are shown by the first five characters of the ATC code by default. If desired this may be changed to a less detailed level with the first four characters of the ATC code so that prescriptions are studied in larger groups of medication. This can be changed in the report showing Relations between a chosen episode (ICPC code) and its percentage with a prescription.

FaMe-Net distinguishes referrals to primary care professionals and to secondary (specialist) care, and the specialisms among these referral types (primary or secondary).

Referral data are a particularisation of the intervention type ‘referral primary care’ (ICPC-2 code *66) and ‘referral secondary care’ (ICPC-2 code *67).

Synonym: contact, consultation.

An encounter is the professional interchange between a patient and a GP. Healthcare provided to patients by other team members of the general practice (practice assistants, practice nurses (Dutch: POH’s), GPs and doctors (in training) are also recorded in encounters. Patients can have contact with their general practice in different ways: physical consultation, telephone consultation, home visit or e-consultation.

We distinguish different types of encounters (encounter types). The majority concerns consultations during office hours. Other encounter types distinguished are home visits, telephone and email consultations (by the GP or the practice assistant), out-of-hours consultations, repeat prescriptions and administrative contacts (specialist letters). They all contribute to the registered morbidity, ordered in EoCs.

One or more Episodes of Care may be dealt with at an encounter. When more than one episode is dealt with during an encounter, there are two or more sub-encounters.Every (sub)encounter has at least one RFE. The only exemption are reports (letters) from other healthcare professionals, which do not have an RFE recorded.

Every encounter results in an (initial) diagnostic label, which is named Encounter diagnosis in FaMe-Net. This Encounter diagnosis may or may not be the final diagnosis (EoC). An Encounter diagnosis could be tiredness, changing later in the Episode to iron deficiency anaemia, and still later to colon cancer. In FaMe-Net’s Episode registration, all these encounters contribute to the Episode (EoC) colon cancer, but we are still able to review the (temporal/preliminary) Encounter diagnoses. In general practice, many Episodes of Care consist of only one encounter.

GPs receive letters from other healthcare providers in primary and in secondary care concerning a patient’s health problem. These letters are added to the patient’s Electronic Medical Record and are assigned to an episode of care.

The information in the letter may result in modifying the diagnosis of the episode of care. A letter may also contain information on a health problem that was not yet known by the GP. In that case, it results in the start of a new episode of care.

General practice emergency care after office hours is provided by a GP medical post. All encounters (physical consultation, telephone consultation, home visit) with this GP post are reported to the GP and recorded in the patient’s electronic medical record. FaMe-Net GPs add the codes for diagnosis, RFE, measurements, interventions performed and medication prescribed during out-of-hours encounters to the patient record.

FaMe-Net has started to collect contextual and personal characteristics of all the enlisted adult patients in a structured way since 2016. Upon invitation by email, patients complete a questionnaire about personal and contextual characteristics, including for example level of education, country of birth of patient and parents, intoxications, psychotraumatic life events, and information on the family history for diabetes, cardiovascular disease and several cancer types.

Patients are invited to update the context survey periodically.

FaMe-Net derives the socio-economic status (SES) from the highest completed educational level, in accordance with Statistics Netherlands’ advice.